Are you wondering if you should use GraphQL in your project? Do you see your developers fight over arguments like “GraphQL is the future” and “REST is just simpler”? I had endless discussion with my team that he will summarize here. Disclaimer: GraphQL is trendy, and you will find countless articles about how it’s amazing, but after 3 years of using it I am a bit bitter and disappointed by the technology, so don’t take my words for granted.

1. Start with Why?

The first question I ask myself before considering a new technology is “Why should I use it?”. For GraphQL, the best way to answer is to come back to the initial problem Facebook was facing. The original post in September 2015, perfectly explains the issue.

“Back in 2012, we began an effort to rebuild Facebook’s native mobile applications. At the time, our iOS and Android apps were thin wrappers around views of our mobile website. While this brought us close to a platonic ideal of the “write once, run anywhere” mobile application, in practice it pushed our mobile-webview apps beyond their limits. As Facebook’s mobile apps became more complex, they suffered poor performance and frequently crashed. As we transitioned to natively implemented models and views, we found ourselves for the first time needing an API data version of News Feed — which up until that point had only been delivered as HTML” We evaluated our options for delivering News Feed data to our mobile apps, including RESTful server resources and FQL tables (Facebook’s SQL-like API). We were frustrated with the differences between the data we wanted to use in our apps and the server queries they required. We don’t think of data in terms of resource URLs, secondary keys, or join tables; we think about it in terms of a graph of objects.

Facebook was facing a really specific problem and build a custom solution: GraphQL.

To expose graph shaped data they designed a Hierarchical query language. In other words GraphQL naturally follows relationships between objects, you can have nested objects and return all of them in one network call.

They built a Protocol, not database. Facebook already had the storage. Each GraphQL field on the server is backed by an arbitrary function that isolates the business logic from the storage.

Finally, with users all around the globe, where cellular data plans are not always cheap, GraphQL protocol was optimized for the mobile customers allowing them to “Only transfer for what they need”.

It’s really easy to understand how GraphQL solves Facebook problems. The remaining question is “Does it solve yours?”

2. GraphQL perks

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

Despite solving a really niche problem, GraphQL convinced a large part of the developer’s community to adopt it thanks to the following perks:

- One request, many resources: Compared to REST where you need to make multiple network calls to each endpoint, with GraphQL you can query all your resources with one call.

- Exact data fetching: GraphQL minimizes the amount of data transferred across the wire by being selective about the data depending on the client application’s needs. Thus, a mobile client with a small screen can fetch less information.

- Strongly typed: Every query, input, and response objects have a type. On web browsers, JavaScript’s lack of type became a weakness that many tools tried to compensate (Dart from Google, TypeScript from Microsoft). GraphQL allows you to share types between the backend and frontend.

- Better tooling and developer experience: Introspective server can be queried for the types it supports, allowing API explorer, auto-completion, and editor warnings. You don’t have to rely on backend developers to document their APIs anymore. You can just explore endpoints and get the data you want.

- Version free: The shape of the data returned is determined entirely by the client’s query, so servers became simpler. When you’re adding new product features, additional fields can be added to the server side, leaving existing clients unaffected.

I perfectly understood those selling points, and I was quite enthusiastic about the technology myself.

3. The Honey Moon

Our mobile team was a strong advocate for GraphQL within the company. Our desktop frontend team also liked the idea of types. We already had a REST API but adopted this technology in 2019. The team invested time in building new endpoints for GraphQL. We chose the Apollo library, which offers React.js, Kotlin, and Swift clients.

The first endpoint was really easy to set up. The Apollo server plays well with express.js on the backend, and the two API Rest and GraphQL endpoints can live together on the same app.

The frontend code became much simpler with GraphQL thanks to “one request many resources.” Consider a situation where a user wants to get the details of a particular artist, say (name, id, tracks, etc.). With the traditional REST intuitive pattern, this will require back-and-forth requests between two endpoints /artists and /tracks that the front would then have to merge together. However, with GraphQL, we can define all the data we need in the query as shown below:

artists(id: "1") {

id

name

avatarUrl

tracks(limit: 2) {

name

urlSlug

}

}

As it went well for the first endpoints, we started adding many more, we had more than 50 in 2020.

4. The Lure of Micro-Optimisation

After two years, I realised that some of GraphQL’s benefits didn’t bring additional value to our project.

4.1. One request, many resources

As mentioned earlier, the main benefit of this pattern is to make the client code simpler. But some engineers wanted to use it to optimise network calls and make the application faster to load.

I don’t think it’s a valid optimisation:

- This is mostly an issue for mobile devices. If you are working on a desktop app or machine-to-machine API, it doesn’t bring any additional value in terms of performance.

- You are not making your code any faster; you are moving the complexity to the backend side that will have bigger compute power. But metrics on our project showed that the REST API stayed faster than GraphQL.

4.2. Exact data fetching

GraphQL aims to minimize the amount of data transferred across the wire by being selective about the data depending on the client application’s needs. A mobile client with a small screen can fetch less information than a larger web application screen. So instead of an endpoint that returns fixed data structures, a GraphQL server only exposes a single endpoint and responds precisely to the client’s requested data.

I don’t think this argument is relevant.

- Not everyone has a mobile and desktop app. This benefit may not even apply to your project. I’ll ignore the argument, “What about smartwatches?”

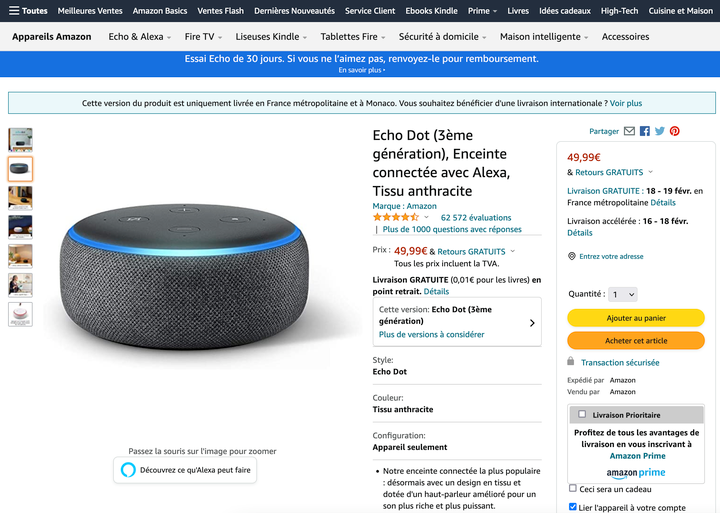

- In theory, it’s interesting but in practice, desktop and mobile applications are similar, and it doesn’t save a lot of data. Let’s take a look at these two examples: Spotify and Amazon.

For the Spotify Album screen, there are only three additional fields on the desktop (number of plays, duration of the track, and duration of the album, so around 30 bytes saved per JSON). For Amazon, there are only two additional data fields on the desktop screen. The Spendesk app is the same and doesn’t actually benefit from this feature to optimise payload size.

If you really want to optimise your loading time, you’d better make sure you download lower-quality images on mobile, but as we will see later, GraphQL doesn’t play well with documents.

On the contrary, GraphQL gives clients the power to execute queries to get exactly what they need. It also means that users can ask for as many fields in as many resources as they want. The query could potentially get thousands of attributes in response, bringing your server down to its knees.

Micro-optimisations tend to be a mistake. You shouldn’t make architectural choices to save milliseconds or a couple of bytes.

5. The Mere Inconveniences

5.1. Strongly typed conundrum

Like WSDL years before, GraphQL defines all the types, commands, and queries of the API in a graphql.schema file. I am a huge fan of typing. However, I found that typing with GraphQL can be confusing.

First, there is a lot of duplication. GraphQL defines type in a schema, but we had to redefine similar types for our backend (TypeScript with node.js) and our mobile apps (in Swift and Kotlin).

To solve this problem, the following two solutions emerged:

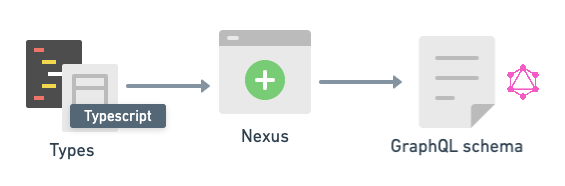

a. Code-first typing

The first solution (like nexus, typegraphql) allows you to declare your types in TypeScript and then generate the GraphQL schema based on them.

Our team tried nexus in 2020 and dropped it after a month. The code was convoluted and didn’t play well with zod.js that we also used for typing. It didn’t support features like federation, and null values were not working correctly. Trying to debug the generated GraphQL schema was not easy. It was a terrible experience, and I wouldn’t recommend it.

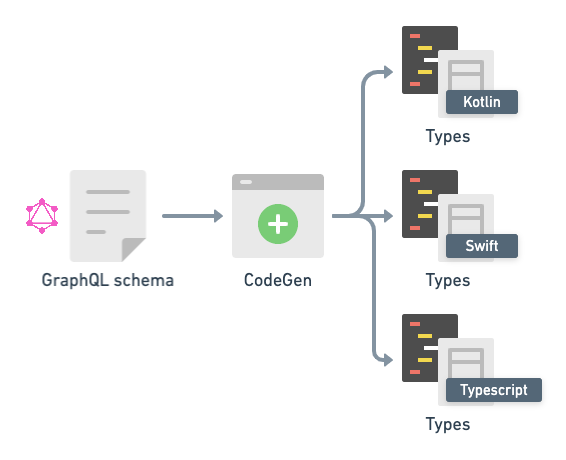

b. Schema first typing The other solution is the opposite; it is used by Apollo (JS) or Ariadne (Python), or CodeGen. First, you build your schema, and a script generates types from the given schema.graphql file.

enum FourEyesProcedureStatus {

VALIDATION_PENDING

CANCELLED

VALIDATED

REJECTED

}

export type FourEyesProcedureStatus =

| 'CANCELLED'

| 'REJECTED'

| 'VALIDATED'

| 'VALIDATION_PENDING';

export type FourEyesStatusEnum =

| 'CANCELLED'

| 'REJECTED'

| 'VALIDATED'

| 'VALIDATION_PENDING';

Types generated for resolvers are convoluted. The problem is for nested objects, where the resolver won’t return the full object. Instead, it will return a partial object and let another resolver complete the other fields.

Typed languages do not support this pattern out of the box. In TypeScript, Codegen ends up putting some any in your code, and creates really complex types.

blockAccount: async (_, args, context): Promise<any> => {}

export type BlockAccountResultResolvers<

ContextType = any,

ParentType extends ResolversParentTypes['BlockAccountResult'] = ResolversParentTypes['BlockAccountResult'],

> = ResolversObject<{

account?: Resolver<ResolversTypes['AccountDetails'], ParentType, ContextType>;

__isTypeOf?: IsTypeOfResolverFn<ParentType, ContextType>;

}>;

For our REST API, we just define internal types and some external DTO. It still has some duplication but remains much simpler than GraphQL.

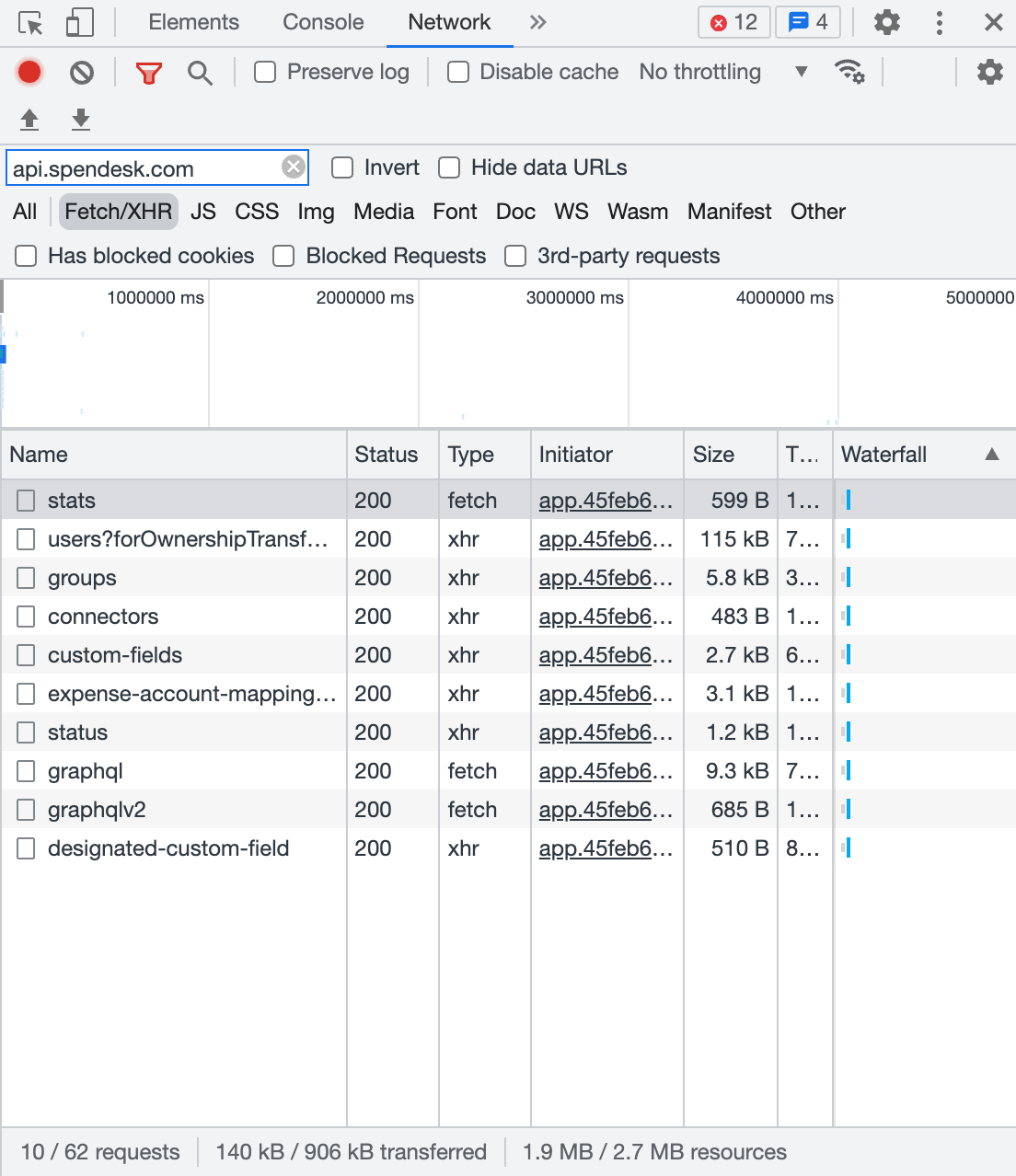

5.2. Better tooling except in Google Chrome

I was skeptical about the tooling because when we started using GraphQL, products like insomnia or Postman didn’t support GraphQL. Now it’s getting better, and they all do it by default.

There is one thing that still bothers me. Debugging is harder. Just look at those two websites, one uses GraphQL everywhere, and the other one has REST endpoints. In Chrome inspector, it’s hard to find what you are looking for, as all the endpoints look the same. In REST, you know which data you are fetching by looking at the URL.

5.3. No support for Error Code

REST allows to leverage HTTP error codes like 404 not found, 400 bad request etc… But GraphQL doesn’t. GraphQL forces you to return a 200 code with an error message in the response payload. To find which which endpoint failed you have to check each payload. Also some objects may be empty because they couldn’t be found or because there was an error. And you can’t make the difference.

5.4 Monitoring

Related to the previous topic it’s really easy to monitor http errors compared to graphQL because they all have their own error code. There is no easy fix for GraphQL. Apollo is working on it and I am sure this one will find a solution soon.

6. The Big Fat Lies

The previous issues are inconveniences. Yet, after three years of using GraphQL, I also discovered some bigger problems.

6.1. Version-free

Nothing is free. While modifying a GraphQL API, you can deprecate some fields but need to be backward compatible. They still need to be there for old clients who are using them. You don’t have to maintain versions in GraphQL, but the cost to do that is that you have to maintain every field.

Just to be clear, REST versioning is also painful, but it provides an interesting property to sunset functionality. In REST, everything is an endpoint, so you can easily block the deprecated endpoints to a new user, and you can measure who is still using the old endpoint.

6.2. Pagination

In the GraphQL Best practices pages, we can read the following:

The GraphQL specification is intentionally silent on a handful of important issues facing APIs such as dealing with the network, authorization, and pagination.

That’s convenient 😅. Overall, you will discover that pagination is painful in GraphQL.

6.3. Caching

Caching aims to obtain a server response faster by saving the results of previous computations. With REST, URLs are unique identifiers of the resources you are trying to access. So you can cache on a resource level. Caching is built into the HTTP specification. Browser and mobile can also leverage this URL identifier and cache resources locally (like they do for images or CSS).

In GraphQL, this becomes complex as each query can be different even though it operates on the same entity. It would require field-level caching, which isn’t easy to achieve with GraphQL since it uses a single endpoint. Libraries like Prisma and Dataloader have been developed to help with similar scenarios but are still far from REST abilities.

6.4. N+1 problems

This problem arises when your data is not a Graph shaped data. Imagine you want to fetch an author and all their books. Storage like SQL would actually store books and authors in different tables.

query {

authors {

name

books {

title

}

}

}

The resolver will look like this:

resolvers = {

Query: {

authors: async () => {

return ORM.getAllAuthors()

}

}

Author: {

books: async (authorObj, args) => {

return ORM.getBooksBy(authorObj.id)

}

},

}

Because the book resolver is called per id, the query would become

SELECT * FROM authors;

SELECT * FROM books WHERE author_id == 1;

SELECT * FROM books WHERE author_id == 2;

SELECT * FROM books WHERE author_id == 3;

We would need to make a call to the DB for each author, losing the ability to use SQL features like SELECT * FROM books WHERE author_id in (1,2,3), where you would make N+1 queries to the DB instead of 2. One solution is dataloader, but it forces you to add another layer of complexity to your code, making it harder to debug performance issues.

6.5. Media types

We have an API to upload documents and display them. GraphQL doesn’t really support uploading documents with multipart-form-data by default. Apollo has worked on a solution called file-uploads, but it is hard to set up. On top of that, GraphQL doesn’t support a media types header when you want to get a document, which allows your browser to display the file properly.

6.6. Security

With GraphQL, you can query exactly what you want, but you should know that this leads to complex security implications. If a malicious actor tries to submit an expensive nested query to overload your server, you will be vulnerable to DDoS (Denial-of-service attack) attacks.

They could also access fields that shouldn’t be exposed. With REST, you can control permission at the URL level. For GraphQL, it has to be at the field level.

user {

username <-- can be seen by everyone

email <-- private

post {

title <-- some posts are private

}

}

7. The Growing Schema Nightmare

As your data graph grows, you can split your data across multiple services. Stitching and Federation are solutions to allow you to split GraphQL schema into smaller ones. But there is a main difference.

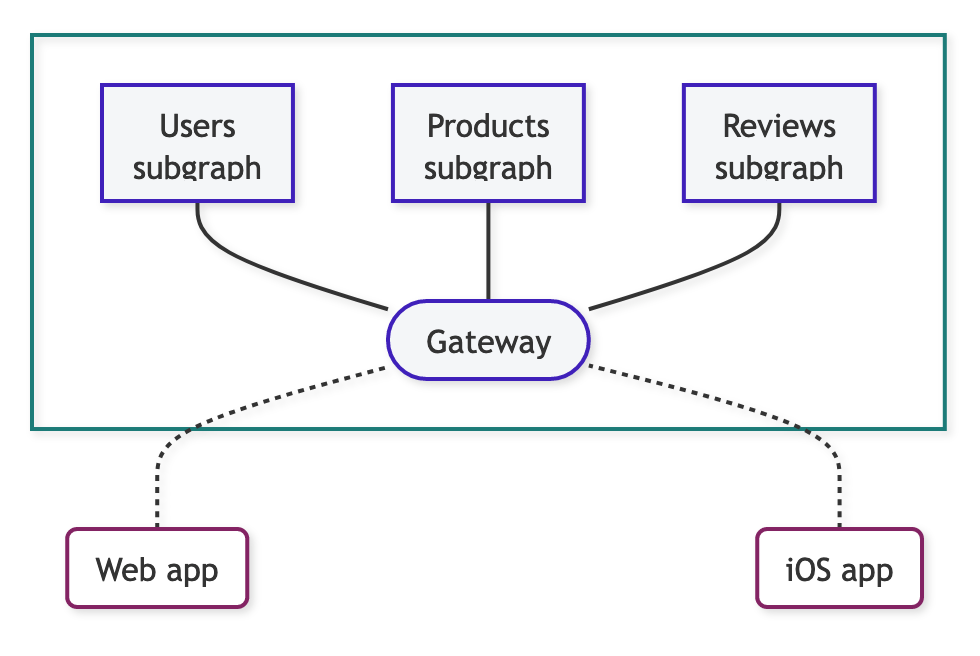

7.1. Federation

Federation assumes a company’s schema should be a distributed responsibility. Here’s what that looks like:

With federation (backed by Apollo), every service is responsible for maintaining its own part of the GraphQL schema. Then the federation server pulls every schema and merges them into a single one.

Federation helps organisations with multiple GraphQL teams to federate a global GraphQL schema.

Federation works well as you stay within GraphQL boundaries. Everything is typed, so it can detect errors easily. You can define @key to join objects across multiple schemas. But it doesn’t support hot reload by default. It means you either need to restart the gateway every time a subgraph changes or you have to use Managed Federation, a proprietary solution by Apollo.

7.2 Stitching

Stitching assumes a company’s schema should be a centralized responsibility.

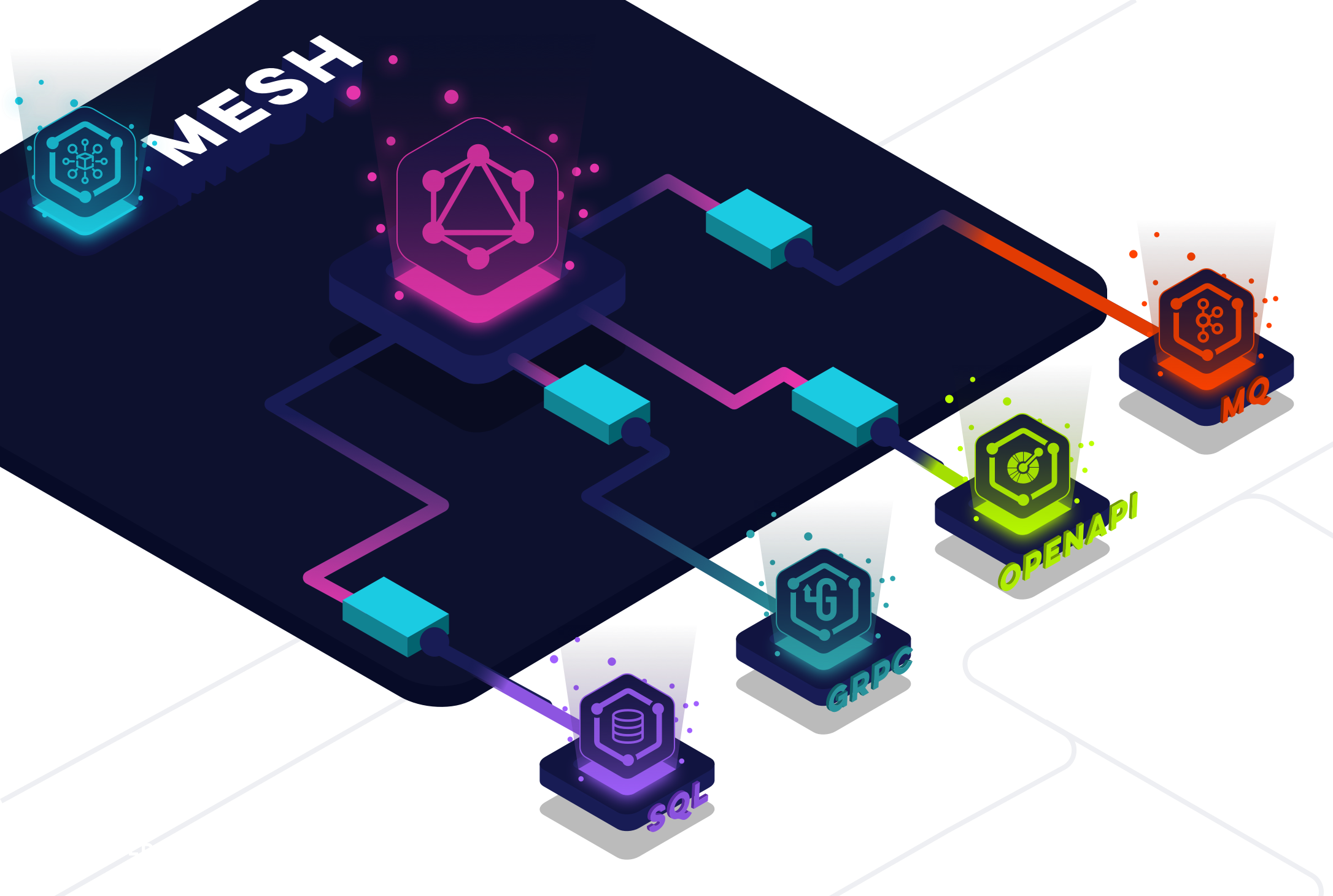

Stitching (backed by mesh, hasura, or stepzen) helps to join across multiple data sources maintained by a central data API team. You define one main GraphQL schema on the gateway and use a resolver to fetch those data automatically from each service that exposes the data (gRPC, REST, SQL).

Stitching is more flexible than federation because it doesn’t force sub-services to use GraphQL. Any data source can be consumed. However, I found that stitching tends to send you toward darker paths, which may include the following:

- Exposing directly an internal database schema directly through your API is a bit dangerous as it creates a strong coupling with the storage. ORM, like Prisma or Graphile, has native integration with GraphQL pushing this idea further.

- Other data sources are not typed, while GraphQL is. So you need to account for extra complexity when some objects have the same name or when you want to join data over a given key.

- You can mix stitching and federation, making it even weirder.

To be fair, both of them are quite complex. This choice is not only a technical one; it links to the structure of your organisation. If teams are independent and you don’t want to enforce GraphQL everywhere stitching is a better solution.

8. The Ecosystem

According to me, the ecosystem is not mature enough, and this is the final challenge.

GraphQL was created internally by Facebook in 2012 and open sourced in 2015. In 2019, Facebook created the GraphQL Foundation, a neutral, non-profit organisation that maintains the specifications and basic implementation for Node.js (graphql.js).

Since then, many actors have appeared, and the ecosystem has become more complex. As of May 2021, there are four other implementations just for Node.js (Apollo, Express, yoga, Helix), six in Go, and four in Python.

Facebook is still quite involved with tools like relay, yet they are not the final decision maker. The ecosystem now counts two other main players:

- The Guild, is a group of open source developers working on a yoda server, mesh, or codegen.

- Apollo is a private company open sourcing their server and clients (Kotlin, iOS, and React) but are selling training and SAAS features like apollo studio and managed federation.

- Other smaller players like hasura.io, stepzen also offer SaaS solutions for GraphQL.

The multiplication of offers makes the ecosystem hard to navigate. I also found it difficult to get clear guidelines. Some actors are not aligned on the future of GraphQL. One interesting point of discord is Stitching vs Federation.

On the opposite side, React, another open source project, is fully maintained by Facebook. It makes it easier to have clear guidelines. When Facebook decided to migrate from class components to hooks, they made it clear. I prefer an ecosystem that converges toward a common solution.

Conclusion

REST was the new SOAP; now GraphQL is the new REST. History repeats itself. It’s hard to say if GraphQL is just a new cool trend that will fade out or a real game changer. One thing is sure, it’s still in an early phase and hasn’t convinced our team yet.

Our mobile and frontend teams at Spendesk love GraphQL. Amazing tooling, the ability to explore the API easily, and strong typing (especially with Kotlin and Swift) make a better developer experience. It makes sense if you think about Facebook’s initial problem. GraphQL was developed to solve a mobile problem. However, those benefits may not be relevant to your project.

Most problems are raised when you start to talk to backend engineers. Lack of proper pagination, caching, and MIME types are real issues. Managing GraphQL types and your native types becomes complex, and the resolver is harder to maintain. As your project grows, you must invest in really expensive tools like Stitching or Federation to fix big schemas. Finally, I think the ecosystem is not mature enough, and the cost of maintaining this solution is too high compared to a REST API.

To make an informed decision, you need to understand your business requirements, especially the shape of your data, where it’s located, who owns it, and who should have access. It also depends on organisational constraints like how many developers you have, are they already comfortable with GraphQL, and the team organisation, as Conway’s Law says organisations’ design systems will eventually mirror their own communication structure.

Razor Modal

Razor Modal