A Norman door is a poorly designed door that confuses or fails to give you an idea of whether to push or pull. It was named after Don Norman, author of The Design of Everyday Things. His book lists best practices to design everyday tools from TV remotes to stoves. In our team, we commit and deploy multiple times a day, so our Continuous Integration Tool is an Everyday Thing. After reading this book, I realised that our CI tool was frustrating and confusing, like a Norman door. Here is the lesson learned and how we fixed our process.

Why do we use Doors?

This sounds like a silly question, but let’s think about it for one second. A door is a tool that separates the “inside” and the “outside” allowing some people through. Not all doors have the same purpose. Prevent access to a secure area, soundproof, keep heat inside a house, or cold inside a freezer. The design of your door will always depend on what you are trying to achieve, and some doors can be poorly designed.

Let’s take an example. This beautiful yellow door looks like a submarine airlock. And thanks to action movies we all know how to open it. We have to turn the wheel. But the message is explicit. “Do Not Turn To Open”. The question remains, how do you open this door then?

Let’s take an example. This beautiful yellow door looks like a submarine airlock. And thanks to action movies we all know how to open it. We have to turn the wheel. But the message is explicit. “Do Not Turn To Open”. The question remains, how do you open this door then?

## Why do we use CI/CD Pipeline?

I hope we all understand the benefits of CI/CD. For me, it mostly reduces the risk of errors, improves velocity and relieves engineering teams from operational work by automating recurrent and error-prone steps. If you want to know more about the benefits and the definition of Continuous Integration, Delivery and Deployment I suggest this excellent article from Digital Ocean “An Introduction to CI/CD”.

Both Jenkins and GitLab (1) have this notion of Pipeline that they defined as “an automated expression of your process for getting the software from version control right through to your users.”

Our team invested a lot of time in automation. After a couple of months, it started to slow us down. We had many problems to maintain our pipeline and frictions during on-call. We introduced a tool to make us fast, but it made us slower. We built what I call a Norman Pipeline.

What’s a Norman Pipeline?

A Norman Pipeline is a CI/CD system that infuriates every developer using it and failing to make us faster and more reliable.

- “Don’t worry the pipeline has been blocked for a while.”

- “I can’t release the pipeline is still running.”

- “The pipeline was blocked but nobody knew.”

- “The pipeline is blocked but the code is working.”

- “Something changed but not sure what?”

- “That’s probably fine some tests are failing randomly.”

- “Just restart the tests it’s a dependency issue.”

If you ever heard this, your CI/CD pipeline is poorly designed. All those quotes were the expression of frustration in our team. So how can we avoid that?

In his book The Design of Everyday Things, Don Norman wrote a chapter on Feedback. An essential notion to design a tool. According to Don Norman, feedbacks need to be:

- A. Immediate

- B. Informative

- C. Consistent

- D. Dosed out

- E. Appropriate

Let’s see how to apply that to our CI/CD pipeline.

A. Immediate Feedback

Our office has a secured door. You can open by swiping your badge on the black reader. Immediately after I swipe, it changes colour to green and unlocks the door. If I don’t have access to this area, it blinks to orange with a warning sound as quickly. I never have to wait!

This is a core concept behind CI/CD. You want to identify the problem quickly. Nobody wants to realise something is broken once customers are using the service. It’s too late.

Most of us build after each commit to make sure the code compiles. Unit-tests give us the shortest feedback loop.

I see the test pyramid as a way to optimise the feedback time. You want tests to fail as soon as possible. That’s why we put fast tests at the beginning of your pipeline, and slow tests at the end.

As we wanted to add more and more tests, we ended up in a common pitfall. We increased coverage from 70% to 95% by doing that we increased the build time from 30 seconds to 3min. What value did that 25% extra coverage bring us? It’s hard to quantify. Did we prevent bugs? Maybe. One thing is sure our dev environment was 6 times slower, and even if 3min is manageable, it can be frustrating.

BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 3m 19s

365 actionable tasks: 298 executed, 67 up-to-date

After increasing the unit test coverage, we went further. As part of the staging step of our pipeline, we introduced “Perf Tests”. We would deploy the code on a specific host and hammer it with requests for 4h until we get the maximum TPS (Transaction per second) for this host.

Max TPS is a piece of valuable information. From this metric, you can deduce how many hosts you need for your peak days. It allows capacity planning. But here is the catch, we made our pipeline slower by 4h. Perf tests are failing the concept of immediate feedback. So it’s better to keep it out of your CI/CD. Instead, we started to run it every day, in parallel, so it would not block the pipeline. If the TPS dropped, you had to dig into 1 day of commit history. It doesn’t tell you accurately which commit made your software slower, but it’s still manageable.

They are also failing the concept of consistent feedback, but I’ll come back to that. Don’t chase the 100% coverage for the sake of it, especially for slow tests like UI, e2e and perf tests.

B. Informative Feedback

The problem with the previous card reader is that the feedback is not informative. New employees don’t know the colour code and are always confused by the orange blinking. They often ask if the door is broken, or if their is badge unreadable? A text message would be more useful.

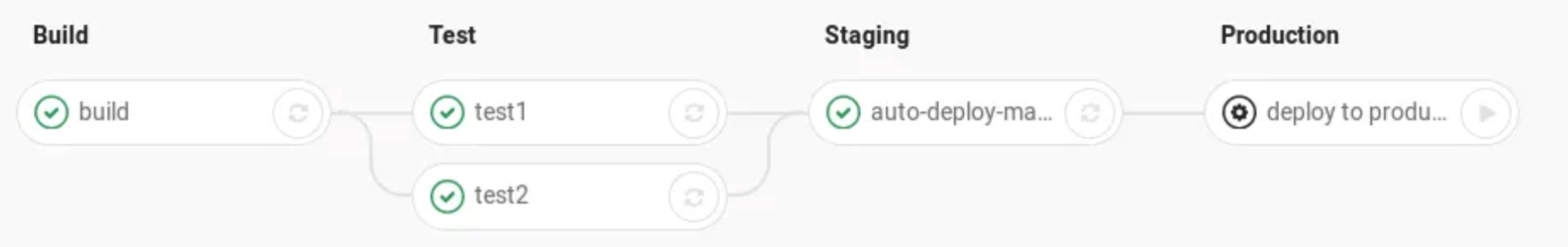

As your pipeline gets more complicated, it will be harder to keep track of what’s happening. What step is currently running? If a test failed, can you identify which one easily? Can you access the corresponding logs in one click?

I like the GitLab interface that displays a clear Graph of what’s happening. Most of the tools provide this kind of visualisation.

Even if unit-tests are easy to reproduce locally, it’s better to have detail about the error. Does it fail because the assertion is wrong, or because of a NullPointerException. For integration tests, it’s more important. Can you capture the logs of the service? Do you know which host was called by the test when it fails?

C. Consistent Feedback

One good thing about this door is the behaviour doesn’t change. If I swipe my badge multiple times, I will get the same results. Moreover, I always push to enter. The colour code is always the same across all the building. All doors behave in the same way.

Once the tests were failing someone reran them, and they mysteriously passed. That is not consistent behaviour. It’s probably better to ignore a test than having a test that fails randomly.

Each microservices had its own pipeline, but they were not set up the same way. The settings of your pipeline are essential, use Infrastructure as code to make sure you can version your changes. GitLab uses a .gitlab-ci.yml file versioned in the repo as part of the code to define the pipeline.

This file lists almost everything about the workflow, but some steps of our pipeline use environment variables. They can only be changed from the interface. Once someone changed a variable and it broke the entire pipeline. It took us a full day to understand. Some pipeline could fail, due to a change of the configuration.

D. Dosed out feedback

If not enough information is bad. Too much feedback can be worse. Your engineers are over flooded by data and don’t know where to look for. Error raised should point the root cause and nothing else.

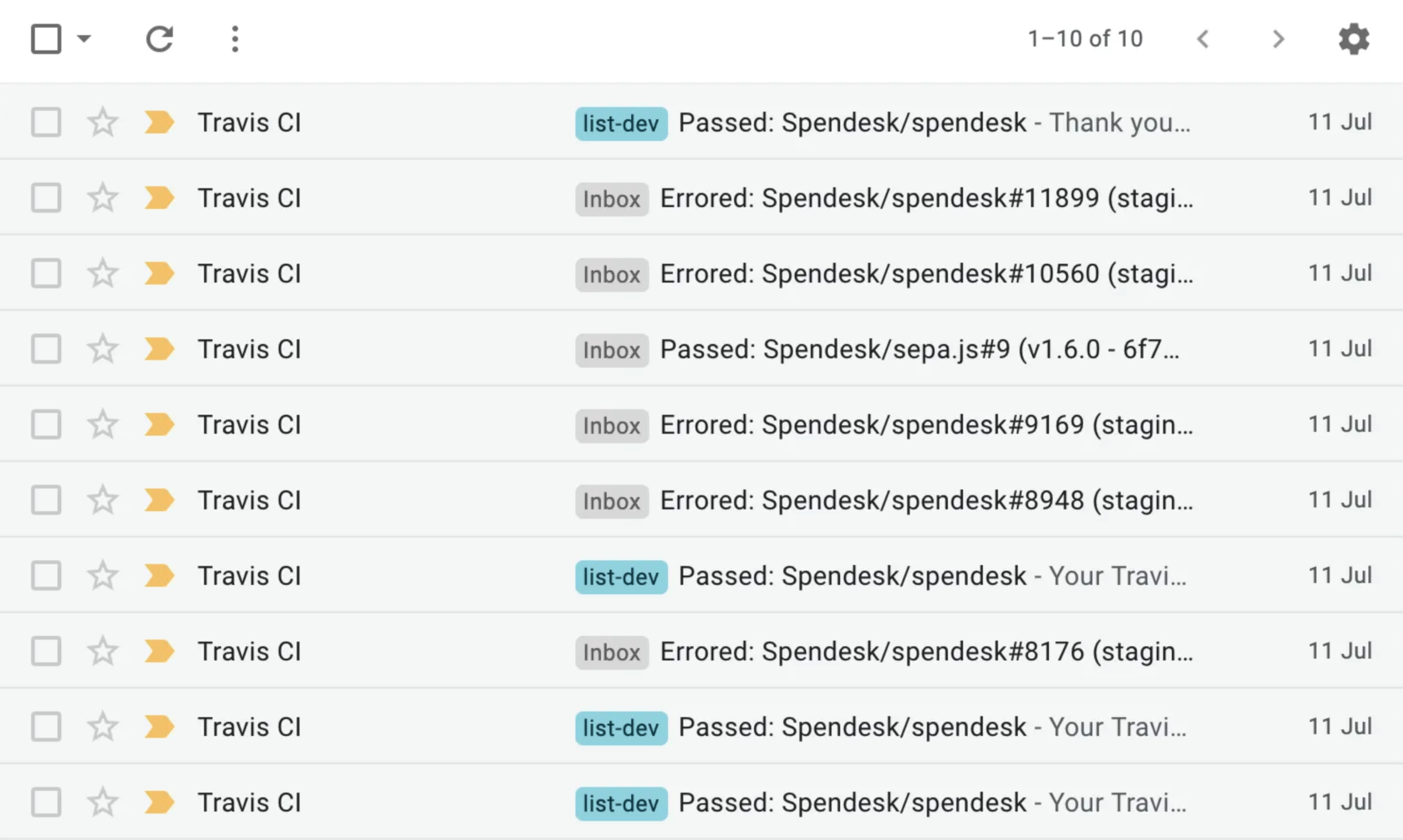

For instance, one of my colleague set up an email notification system. Every time the pipeline was running, succeeding, or failing, we would get an email. This became just another spam we learned to ignore or automatically delete.

I usually don’t need to know when everything is ok. Another issue is to send the notification to our mailing list (list-dev). Because the message is broadcasted, there is no owner. We want to make sure that when the pipeline is blocked, then someone takes care of it. So we put in place targeted notification. When someone pushes a code that breaks the build, he is the only one notified, he is then responsible for unblocking it.

E. Appropriate Feedback

The Three Mile Island nuclear accident occurred on March 28, 1979, in reactor number 2. The leading cause for the incident was a poorly designed interface. Indeed the first problem was due to a technical failure on a non-nuclear secondary system, a valve of the cooling system was stuck open. But the corresponding indicator light on the control panel was indicated the valve was closed. (To quote Wikipedia: “In fact the light did not indicate the position of the valve, only the status of the solenoid being powered or not, thus giving false evidence of a closed valve”. [21])

Due to this false value, the human operator mistakenly believed that there was too much coolant water present in the reactor and causing the steam pressure release, so the operators did not correctly diagnose the problem for several hours.

We had a more recent example of bad design leading to wrong feedback in 2018 when a human operator triggered a false missile ballistic alter in Hawai.

Obviously, those 2 examples are extreme, but the idea remains the same. You need clear feedback. If a test fails, you want to be able to identify quickly which one.

Our E2E tests were running in parallel to speed them up, but they were all depending on the same pre-prod database. If the database were down, all the tests would fail, and it was tough to understand why. To solve that we added an integration-test checking the database first and stop the pipeline in case of a problem. We did the same for all our dependencies.

Conclusion

A CI/CD is a fantastic tool. It’s just hard to get it right. Especially in a company like Amazon, where software engineers are also DevOps. You don’t have dedicated SysOps in charge of that. If you want to spot the problem, the easiest way is to listen to your engineers. Come back to the quotes I listed previously.

- “Don’t worry the pipeline has been blocked for a while.”

- “I can’t release the pipeline is still running.”

- “The pipeline was blocked but nobody knew.”

Those are clear, Immediate feedback issue. Make your pipeline run fast and fail fast. Make it visible when it’s blocked. You don’t want to find out when you are trying to release a hotfix.

- “The pipeline is blocked but the code is working.”

- “Something changed but not sure what?”

Here is the usual ‘Informative feedback’ issue. Your pipeline should help you to diagnose what’s wrong, not riddle you. You actually can find the same problem in the way you log.

- “That’s probably fine some tests are failing randomly.”

- “Just restart the tests it’s a dependency issue.”

Those final ones reflect a problem with ‘Consistent feedback’.

A CI/CD pipeline is supposed to make you save time, but when poorly designed, it will become a nightmare to maintain and will frustrate devs working with this “everyday tool”.

Book By Don Norman — (Credits: By Source, Fair use Wikipedia) (1) Disclaimer: There are a lot of Continuous Integration Tools out there. I am not going to argue which one is the best. I will try to be generic. I will list broken designs cross-platform. But for specific examples, I’ll use GitLab because that’s the one I used most.

(2) Some people say CD means Continuous Delivery instead of Continous Deployment. There is a slight difference, but I do sometimes use them interchangeably.

(3) Disclaimer: This article is a personal reflection that doesn’t represent my previous or current employer.

Razor Modal

Razor Modal