Amazon owns hundreds of Fulfillment Centers (FC) that contain up to a billion units. To give you a better idea an FC is larger than 15 soccer fields.

Catalog, Inventory, and Offers

Let’s define a couple of terms first

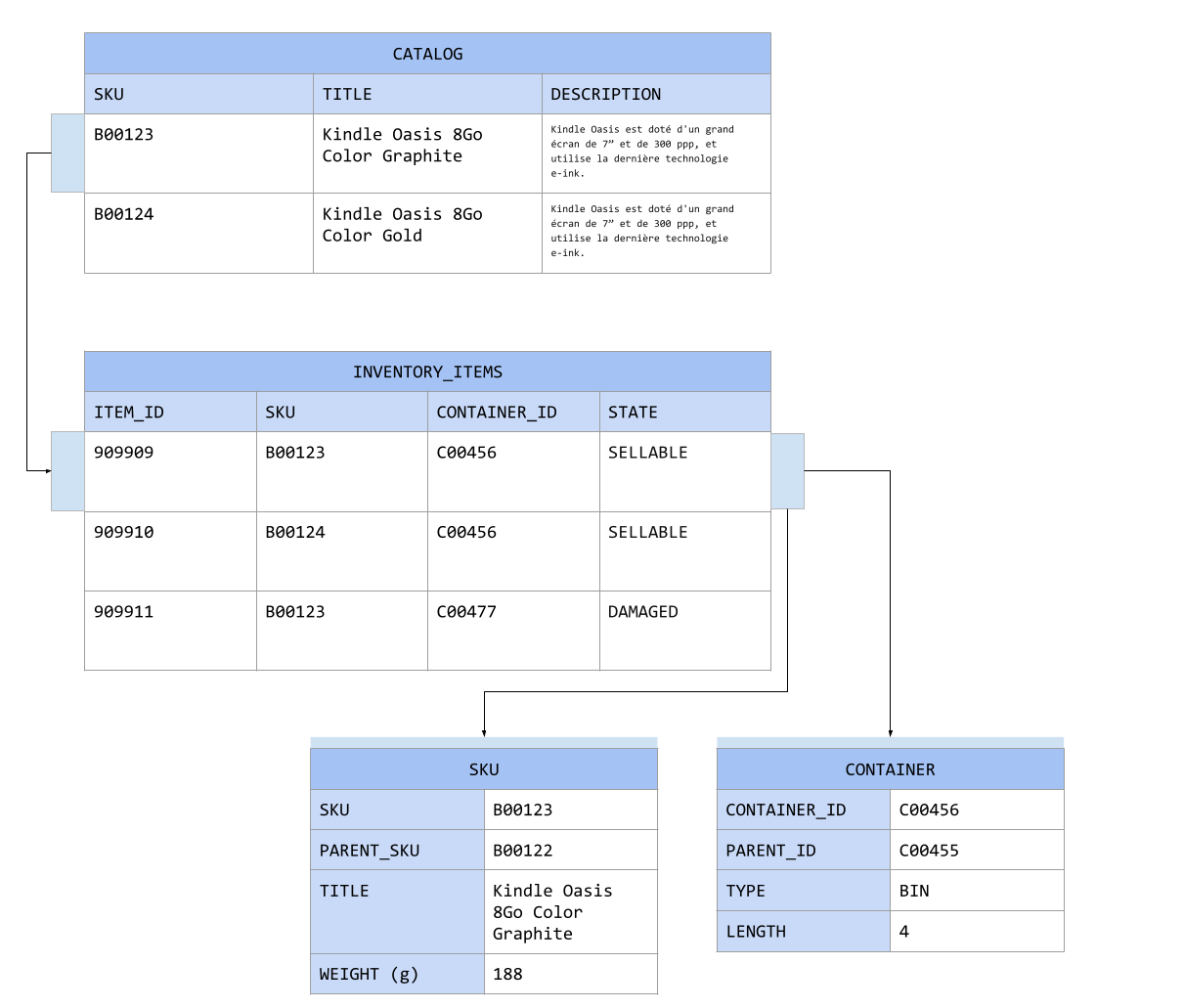

The catalog lists all the products available on a retail website. A product describes a physical item (cover, summary, author for a book). The inventory lists what is physically in the warehouse, it contains physical items usually described by their weight, size… An offer is an option to buy a given product at a point in time for a given price. For instance: If you sell a Kindle Oasis 8Go color Graphite, this is the reference of your product that will be listed in the catalog. If you have 1000 of them in a warehouse, then each physical items are listed in the inventory.

It’s important to understand that a product reference can be in the catalogue but not in the inventory (out of stock, lost). An item can be in the inventory and the reference not in the catalog (product recalled for safety reasons, consumables expired).

The Kindle Oasis 16Go color Graphite and the Kindle Oasis 8Go color Gold are two different products.

It’s also essential to differentiate the price from the inventory. For instance, a Kindle Oasis 16Go color Graphite is sold 249.99$ on amazon.com, the same product can be sold 199.99$ on black Friday, or 249.99£ on amazon.co.uk, or it’s sold 259.99$ with a bundle of 3 books. Each price is a different offer for the same product. Offer depends on the merchant, the date, the user.

Physical vs Digital

So far I only mentioned physical items. Amazon also sells digital items. If you want to read Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, you could buy the physical book from the publisher Bloomsbury Children’s Books, or the special Ravenclaw hardcover edition from Educa Books. But you can also buy the digital version. Obviously, digital items are handled differently so I will ignore this complexity in the rest of the article and focus on physical items.

Naive Inventory Model

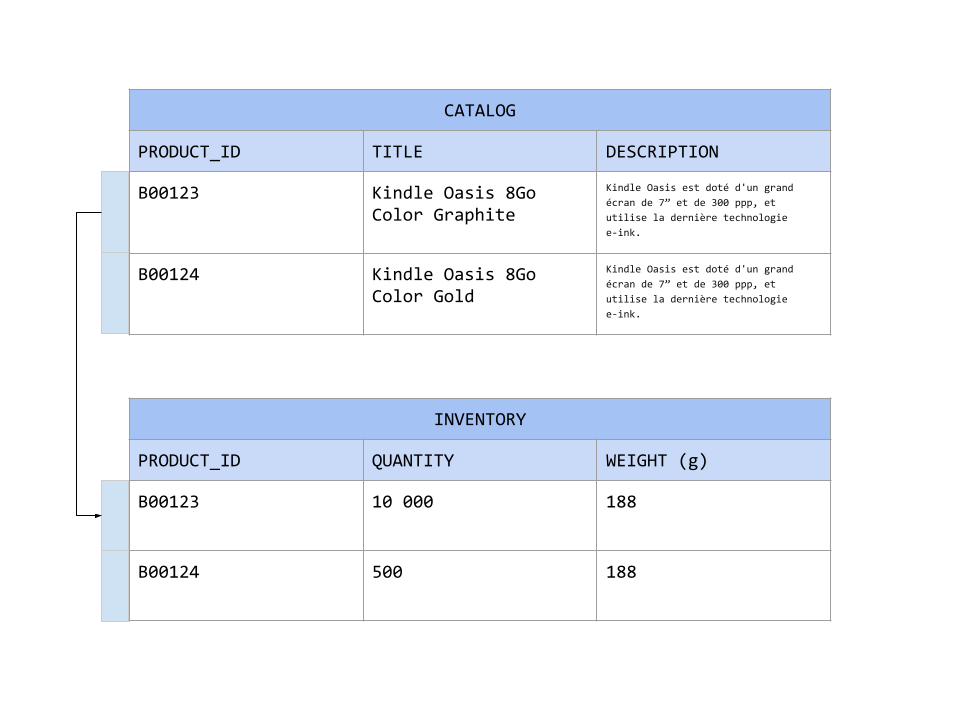

The first try to model an inventory usually looks like this: Let’s assign an id to every product in our catalog. We will call it the product_id. Let’s use this key to map a row in the inventory that contains the quantity in stock.

Naive inventory

Naive inventory

This model has 2 massive flaws:

- First, it assumes items are interchangeable. You could argue that most of the time it’s true. When you buy a Kindle from a shelf at John Lewis, you just pick the first one. But in a warehouse, anything can happen. An item can be damaged by a conveyor belt. You need to track them individually. Moreover, consumables have an expiration date. So a bottle of olive oil that expired on the 1st of October 2020, is different from one expiring on the 1st of October 2021.

- Second, it assumes that all the items are stored in the same place in a warehouse. Like in a library where all the harry potter books are on the same shelf. Unfortunately, that’s a false assumption. Items are stored where there is space left in the warehouse. So you need to know where they are so you can go find them.

🤯 Fun fact: An effective storage method is random, it voluntarily avoids putting all the same items at the same place. Fire and water leak are localized incidents, if all the Harry Potter books were at the same place it would destroy your entire stock. It’s better if they destroy one item of each. Randomness spread them across a warehouse to improve resilience.

Improved Inventory Data Model

To avoid the 2 previous flaws, here is an improved data model.

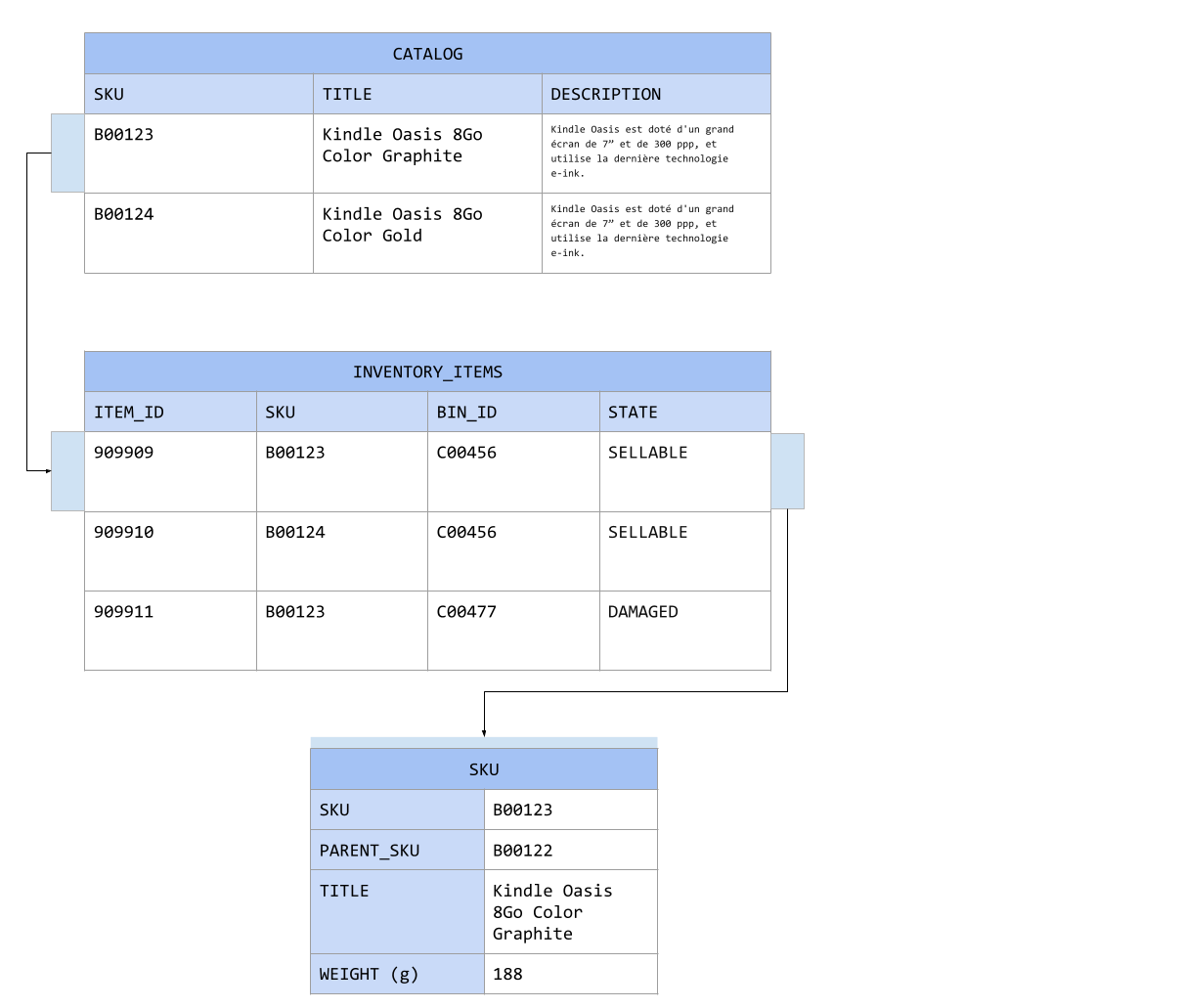

Stock Keeping Unit (SKU)

The Stock Keeping Unit (SKU) “is a distinct type of product for sale and all attributes associated with the product type that distinguish it from other types. It could include manufacturer, description, material, size, color, packaging, and warranty terms.”

This is basically what I called before the product_id. From now I will use SKU as it’s a known convention in the supply chain industry.

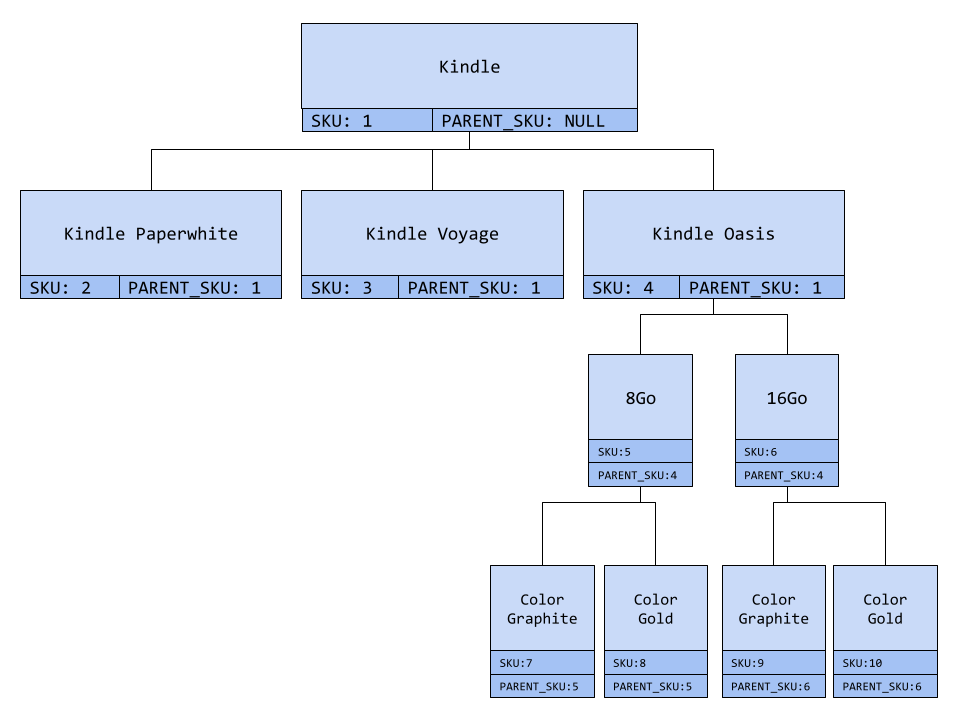

Parent SKU

As you can see, this model introduces the parent_sku. It allows you to create a tree of product and group them by category.

With this tree you can implement fine grained catalog search. It’s also convenient from the storage point of view. For instance, if you want to recall an entire product line you can find all of them using the parent SKU.

🤯 Why SQL? This is a valid point, with billions of items, key-value storage could feel more scalable. We could argue that the size of a warehouse is fixed, and so the inventory has a hard max limit of items it can contain. But the real reason is that key-value storage was not a thing in 1996. The first Amazon warehouses were running on Oracle databases.

Scale your Physical Storage

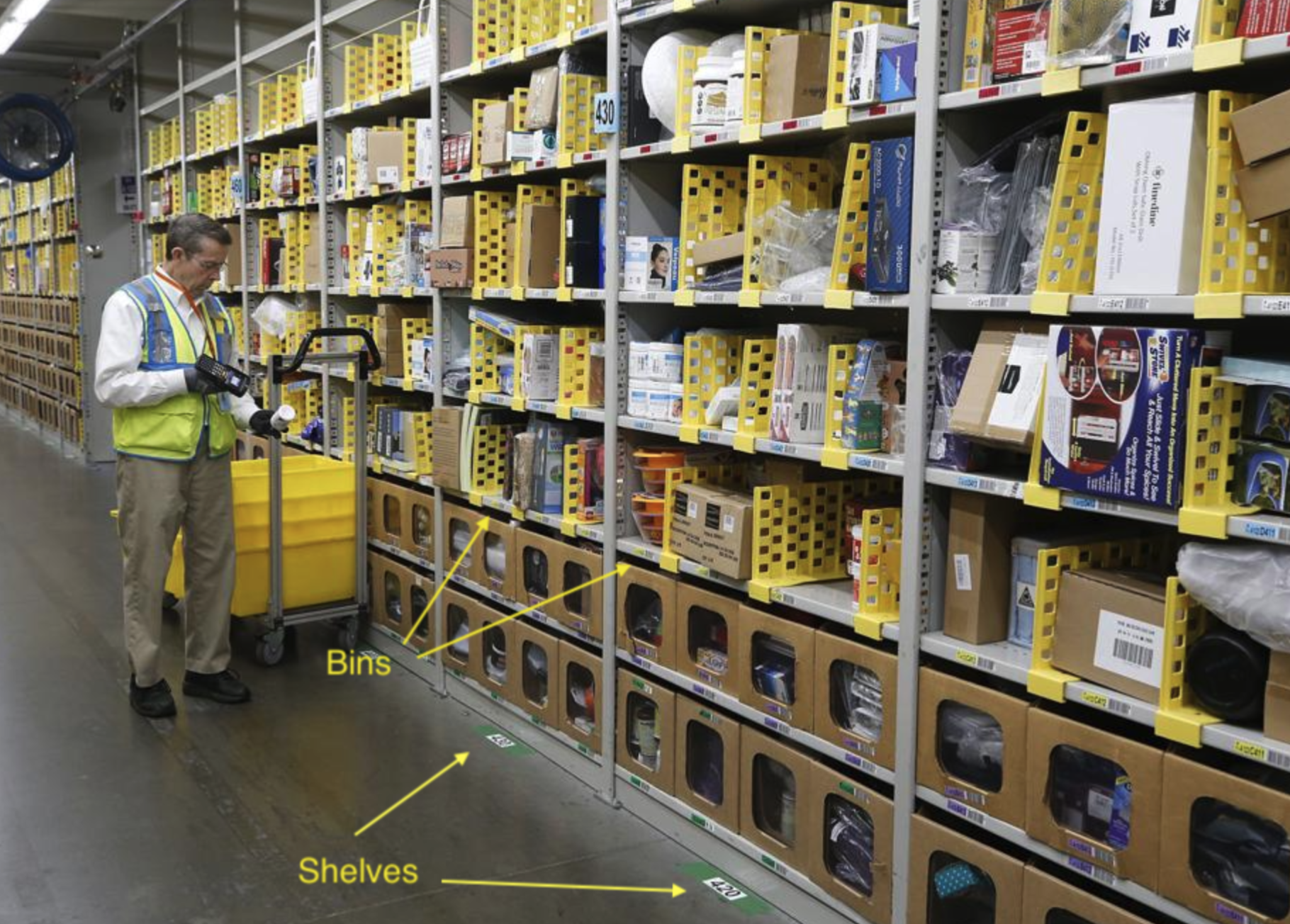

If an ideal warehouse looks like shelves and bin, this storage system is not flexible enough. It requires pickers to unpack every item to put them in a specific bin. So let’s introduced the notion of pallets that allows fast storage.

Bins are delimited by yellow separations.

Bins are delimited by yellow separations.

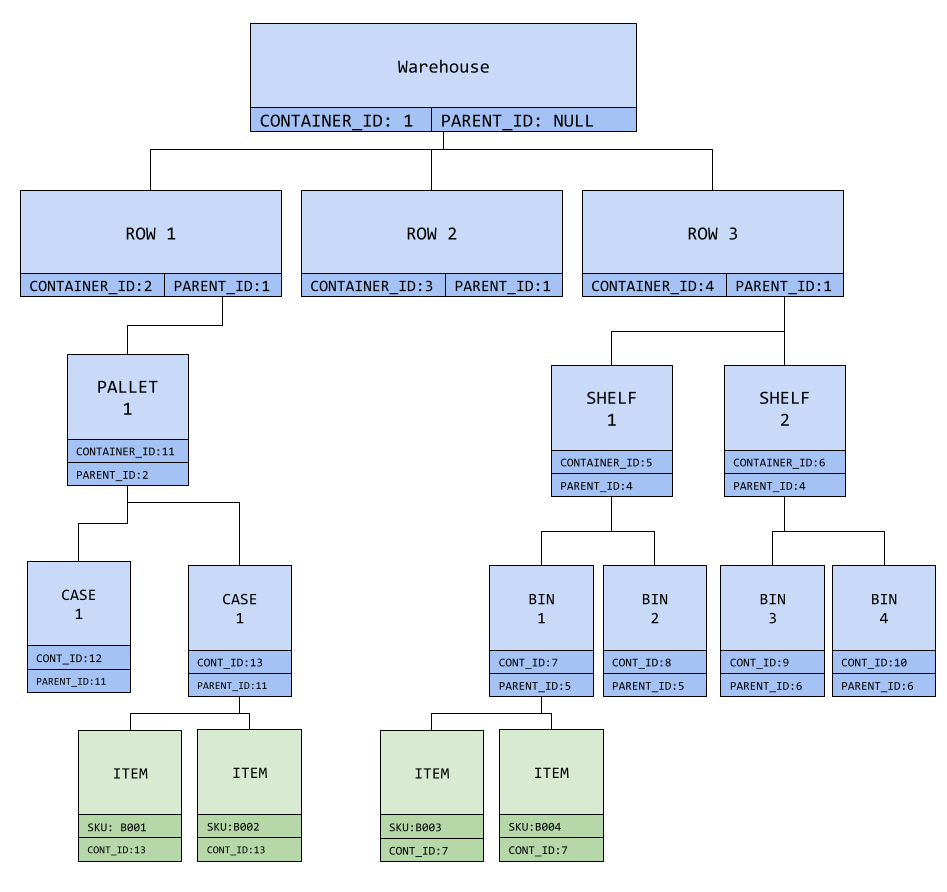

- BINS: container on a shelf to store small items (books, DVD).

- PALLETS: are stored directly on the floor, and contains multiple cases each of them can contain many items, usually of the same product.

Bins are delimited by yellow separations.

Bins are delimited by yellow separations.

To update the model to fit this new requirement, we introduced a table called CONTAINER.

Same here we use a tree structure to map the warehouse, as a BIN can be on a shelf, which is part of a ROW. The length can tell you how many items are in the BIN. The same applies for a palet, as an item can be in a case, that is stored in a pallet located in a given ROW.

We solved the two previous problems, now each item is uniquely identified in the warehouse at a specific location. Moving an item requires changing the container_id, moving a pallet is simple too just change the parent_id.

But this model creates a lot of different problems. What if we want to locate a given item so it can be delivered? Do we need to go through all the item then go upward on the tree?

How do you deal with concurrency? Someone could be moving boxes from a pallet at the same time someone is picking one item from a box in the same pallet.

Merge the Trees

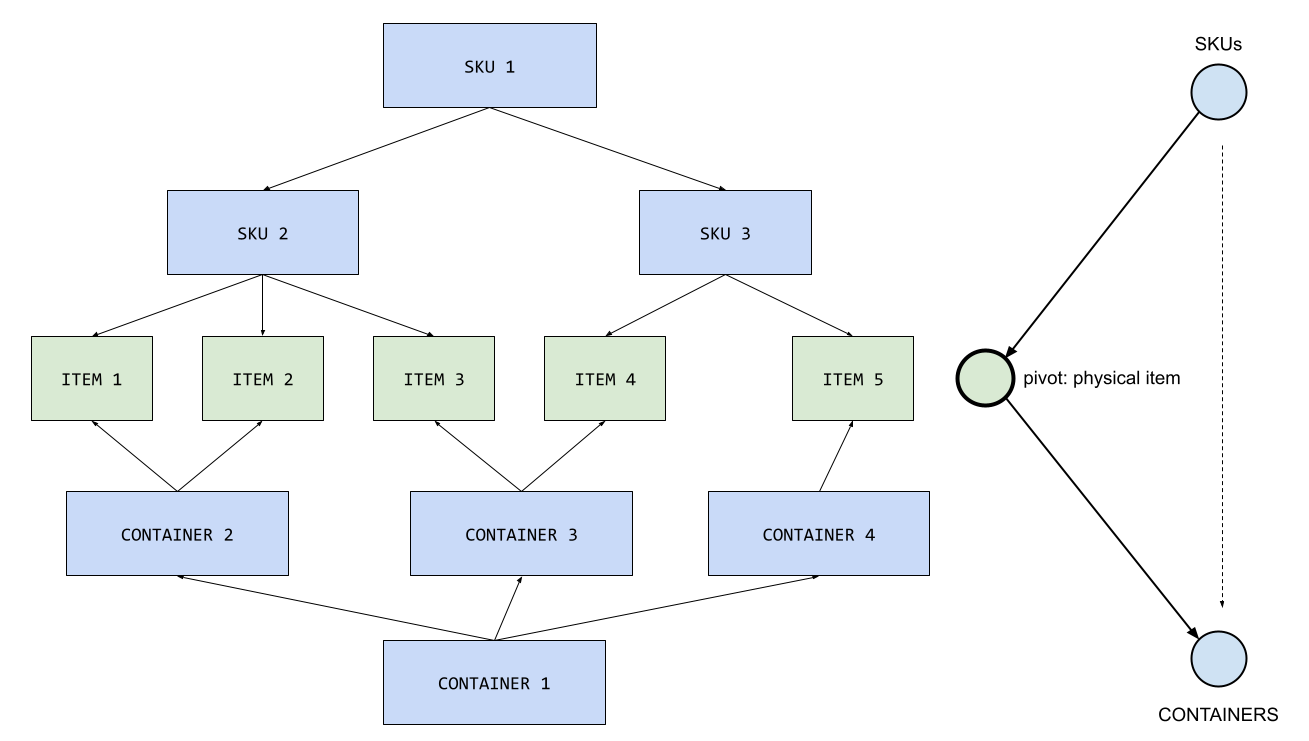

That idea is to merge the two previous tree structures. Based on the Pivot that would be the physical item itself. This is a powerful idea to have 2 parents for physical items.

By using the layout of 2 trees, one top-down and the other one bottom-up some complex operations become easy. If we go back to the previous example: locating an item is just going down the graph from the SKU. If we want to list all the products in a given container we move up the graph.

Same if you want to recall all the expired items in the warehouse. You would just need to do a search in this tree.

You also solved your concurrency issue, as moving a pallet is now an ATOMIC operation in your SQL DB. The tree is modelled in a single table that would look like that.

A tree as a SQL table.

A tree as a SQL table.

UPDATE PARENT_ID=CONTAINER_05 from CONTAINERS where ID=CONTAINER-03;

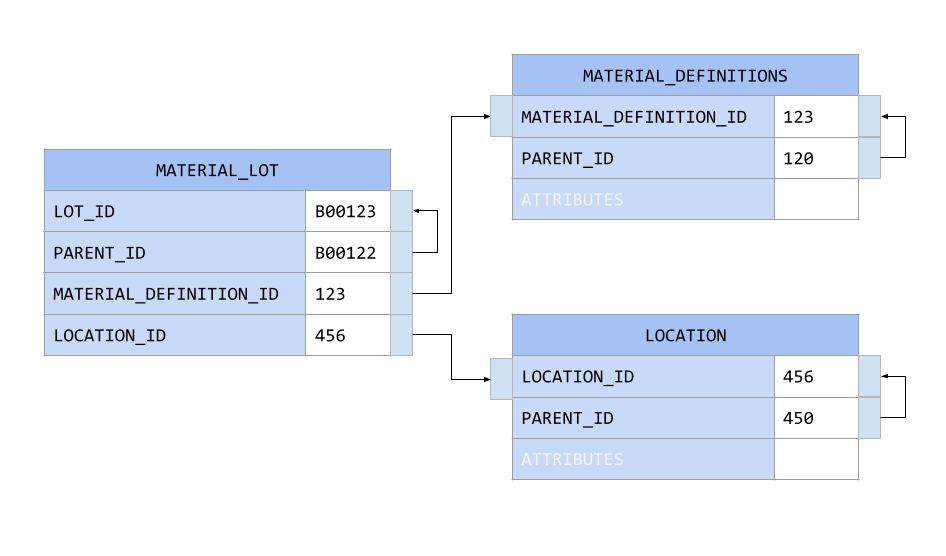

🤯 Fun Fact: Amazon didn’t invent inventory, there is a Standard in the industry call ISA-95. It’s actually part of a wider standard used for manufacturing. They define MATERIAL_LOT (correspond to the physical item) has 2 parents one MATERIAL_DEFINITION that describes the item, and a LOCATION that tells you where it is (corresponds to CONTAINER). Each of those 3 concepts has a recursive tree that allows multiple levels of precision as we’ve seen before.

ISA-95 norm for the manufacturing industry.

ISA-95 norm for the manufacturing industry.

Final Words

Congrats if you managed to make it so far. Unfortunately, this is just the tip of the iceberg. A warehouse is a complex environment and I ignored many of the difficulties a software engineer will be facing.

First, I talked about containers like BINS or PALLETS. But I didn’t mention their physical location inside the warehouse. If you want to move a pallet, you first need to know where it is and where it should go. How do you find an empty space for a given pallet?

Second, I assumed every item fits in a BIN, and every PALLETS has the same size. That’s unfortunately incorrect. To optimize space, you may want to put small items together.

Then I ignored the role of pickers. You know the person who walks into a warehouse and gets your item from the BIN. You want to optimize the time for them to get items.

A warehouse is not a computer. There are a lot of things that can go wrong. Items can be damaged, lost. You can get deliver the wrong order, someone can make a mistake in the packaging. Your code need to be resilient in many ways and we will talk about all this problem in a future article.

Photo by Marcin Jozwiak on Unsplash

Razor Modal

Razor Modal